Laryngeal tuberculosis in renal transplant recipients: A case report and review of the literature

DOI:

https://doi.org/10.17305/bjbms.2020.4448Keywords:

Laryngeal tuberculosis, kidney transplant, laryngeal leukoplakiaAbstract

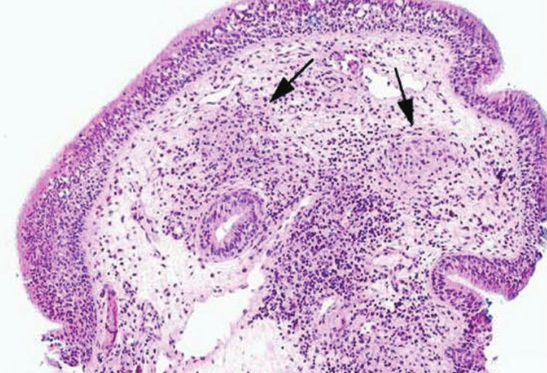

Renal allograft recipients are at greater risk of developing tuberculosis than the general population. A woman with a kidney transplant was admitted to our emergency department with high temperature, dysphonia, odynophagia, and asthenia. The final diagnosis was laryngeal tuberculosis. Multidisciplinary collaboration enabled accurate diagnosis and successful treatment. Laryngeal tuberculosis should be considered in renal allograft recipients with hoarseness. A more rapid diagnosis of tuberculosis in renal transplant recipients is desirable when the site involved, such as the larynx, exhibits specific manifestations and the patient exhibits specific symptoms. In these cases, prognosis is excellent, and with adequate treatment a complete recovery is often achieved.

Citations

Downloads

Downloads

Additional Files

Published

Issue

Section

Categories

License

Copyright (c) 2020 Fabrizio Cialente, Michele Grasso, Massimo Ralli, Marco de Vincentiis, Antonio Minni, Griselda Agolli, Michele Dello Spedale Venti, Mara Riminucci, Alessandro Corsi, Antonio Greco

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.

How to Cite

Accepted 2020-02-20

Published 2020-08-03